1860: Fackler v. Ford. This U.S. Supreme Court case was brought over an allegation that a contract to sell land was in violation of a treaty with the Delaware Indians and an act of Congress. The issue was an act of fraud on the part of the seller of the property. Opinion.

1866: The Kansas Indians. The U.S. Supreme Court held that the State of Kansas lacked authority to tax lands held by individual Indians of the Shawnee, Wea and Miami tribes that had previously been held by the tribes. Opinion.

1878: United States v. Fort Scott. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the City of Fort Scott was obligated to repay the principal and interest on bonds issued for public improvement. To repay the bond holder, Concord Savings Bank, the city was required under the provisions of an 1871 law to tax all property holders in the city to generate sufficient revenue to repay the debt. Opinion.

1884: Foster v. Kansas. Attorney General William Agnew Johnston began proceedings in the Kansas Supreme Court for the removal of Saline County Attorney John Foster. At issue was Foster’s neglect and refusal to prosecute individuals guilty of selling liquor in violation of state prohibition laws. Foster challenged whether the law allowing for his removal was constitutional. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the Kansas Supreme Court’s denial of Foster’s motion to dismiss the case. Opinion.

1884: Ames v. Kansas. The question of original jurisdiction was raised after the State filed suit against the Kansas Pacific Railroad Company over consolidation of the corporation with the Union Pacific Railroad. The issue was the right of the Kansas Pacific to consolidate and reorganize operations under Kansas law. On appeal, the question settled was whether the U.S. Supreme Court could exercise original jurisdiction exclusively in the case because the railroad was originally granted articles of incorporation by Congress. Opinion.

1896: Lowe v. Kansas. The U.S. Supreme Court held that the due process rights of a county attorney were not violated when he was ordered to pay the legal fees for a defendant in a libel case originating in Chautauqua County. The court upheld Kansas law requiring a prosecutor to pay the fees when the charges were brought without probable cause or with malicious intent against a defendant. Opinion.

1902: Kansas v. Colorado. This original action filed in the U.S. Supreme Court would begin more than 100 years of legal battles between the two states over rights to water in the Arkansas River. Kansas filed its complaint in 1901 claiming that Colorado was diverting more than its fair share of water as it coursed east some 200 miles from the headwaters in the Rocky Mountains to the Kansas border. The suit claimed that Colorado's actions deprived Kansas of millions of dollars in state revenues for general government and schools. Colorado objected to the Kansas suit. The justices agreed with Kansas that it had a right to the waters that was being used or diverted in Colorado. However, the justices declined to make a ruling on the case, citing the need for additional fact finding to determine the nature of the damage to Kansas and what actions, if any, Colorado must suspend. Opinion.

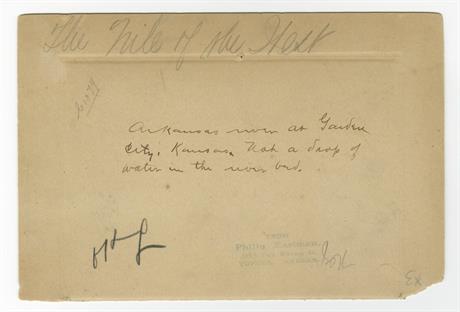

A photograph from Garden City, Kansas taken in the late 1800s shows the dry riverbed of the Arkansas River, "The Nile of The West". Colorado's diversion of water upriver caused

considerable harm to Kansans further downstream, who depended on the Arkansas to support the agriculture of the region. This underlying issue in the 1902 Kansas v. Colorado case

would still be in dispute nearly a century later. (Photo credit Kansas State Historical Society)

1907: Kansas v. United States. The state sued the United States arguing a matter related to the disposition of land that was awarded during territorial days for the establishment of railroads. The land in question had previously been Indian Territory. The U.S. Supreme Court didn’t rule on the merits of the case, but ruled against Kansas on the grounds states could not sue the federal government. Opinion.

1907: Kansas v. Colorado. A lawsuit filed by Kansas over Colorado’s use of the Arkansas River was once again brought before the U.S. Supreme Court. After weighing the arguments by Kansas and reviewing the statistical data provided on stream flow and crop yields, the justices dismissed the case without prejudice. The justices left open the possibility for Kansas to bring new action when it became evident that Colorado’s depletion of the Arkansas River was being done to the detriment of Kansas’ agricultural and financial interests. Opinion.

1908: Coleman v. MacLennan. Chiles Crittendon Coleman was Kansas attorney general from 1903 to 1907. When he was seeking a second term in 1904, Coleman became the subject of intense criticism by the publisher of the Topeka State Journal, F.P. MacLennan, regarding his involvement with the state school fund. Coleman later sued MacLennan claiming the article to be libelous and sought damages and that the publication was the “fruit of malice”. MacLennan argued that the publication was privileged and meant to inform voters as to Coleman’s character as they decided the 1904 race. Coleman was reelected to an additional term in office despite the publicity. Although this case was decided by the Kansas Supreme Court and never reached the United States Supreme Court, it later gained national significance when the United States Supreme Court cited it in the landmark 1964 case N.Y. Times v. Sullivan for the origin of the term “actual malice” in the First Amendment law of defamation. Opinion.

1909: Missouri v. Kansas. At issue was the boundary line between the states and the ownership of islands in the channel of the Missouri River. The case revisited where the initial lines were drawn when Missouri entered the Union and the lands to the west were considered the frontier. Opinion.

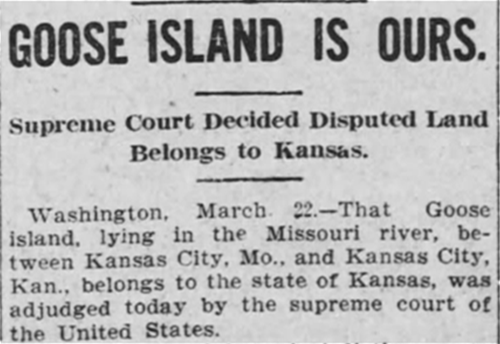

A March 22nd, 1909 newspaper clipping from the Topeka State Journal proclaims victory for Kansas in Missouri v. Kansas. The case marked the first in a series of Supreme Court cases centered around a border dispute between the two states. At the center of the 1909 case was the ownership of Goose Island, a 400 acre islet that--because of the dispute over jurisdiction--had become a haven for criminal activity. (Photo credit newspapers.com, Kansas State Historical Society)

1914: German Alliance Insurance Co. v. Ike Lewis (Superintendent of Insurance). The U.S. Supreme Court upheld a 1909 state law that allowed Kansas to exempt German Alliance, a farmers’ mutual insurance company insuring only farm property, from regulation of fire insurance rates. The legal question was whether the Kansas statute denied equal protection to other insurance companies that provide the same types of coverage as those exempted. Opinion.

1915: Kirmeyer v. Kansas. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the right of Kirmeyer to operate a beer distributorship. Kirmeyer moved his operations to some extent across the Missouri River to Stillings, Missouri, while maintaining operations in Leavenworth. Missouri was a wet state and Kansas dry. The court ruled that Kirmeyer was protected by the commerce clause to operate his beer distributorship legally and was not in violation of the Wilson Act. Opinion.

1917: Wear Sand Co. v. Kansas. This litigation addressed whether the state could charge a fee for allowing a company to dredge sand from the Kansas River. At issue was whether the practice of ad filum aquae that dated to English law before the Magna Carta applied to the Kansas River. The river was deemed non-navigable by the Kansas Legislature in 1864, but it was still considered to be a public waterway and not subject to the taking of adjacent landowners. The U.S. Supreme Court thus held that the state acted lawfully to charge for extraction of sand from the river. Opinion.

1923: Charles Wolff Packing v. Court of Industrial Relations. The U.S. Supreme Court reversed the Kansas Supreme Court’s ruling that affirmed a decision by the state Court of Industrial Relations that had forced the Charles Wolff Packing Company to increase its wages under the guise of public interest and the obligation for state regulation. The decisions of the Court of Industrial Relations were binding arbitration, though appeal to the Kansas Supreme Court was permitted. The U.S. Supreme Court reversed the decision on grounds that the 14th Amendment rights of the packing house were violated by depriving it of its property and “liberty of contract without due process of law.” Opinion

1939: Coleman v. Miller. This landmark case settled the question regarding time limits for the ratification of constitutional amendments. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that it was a political question not a legal question and that Congress had the authority to place time limits on ratification. The amendment in question in 1939 was the Child Labor Amendment which had been rejected in 1925 Kansas but later ratified in 1937. The case was brought by Rolla Coleman and other members of the Kansas Senate against Secretary of State Clarence W. Miller to void the Senate’s approval of the amendment. Opinion.

1944: Kansas v. Missouri. For the second time in less than 40 years, Kansas and Missouri were involved in a legal border war. The dispute again centered on the border as it pertained to the Missouri River. A special master was appointed by the U.S. Supreme Court to settle the dispute, resulting in a decree issued June 5, 1944. Opinion.

1950: Kansas v. Missouri. The U.S. Supreme Court affixed the border of Kansas and Missouri to complete the legal proceedings that began with the court’s decree in 1944. The order was issued after the 1944 agreement was agreed upon by the Kansas and Missouri legislatures, the U.S. House and Senate and the President of the United States. Opinion.

1954: Brown v. Board of Education. There were 11 cases that challenged school segregation in Kansas between 1881 and 1949. Kansas law was silent on the issue of segregated schools until passage of a law in 1877 that permitted, but did not require, segregated schools in communities with populations of 15,000 or more. In this landmark decision, the U.S. Supreme Court forced the desegregation of public schools and held the doctrine of separate but equal facilities violated the 14th Amendment. Historians have called the opinion the greatest ruling of the 20th century for its impact on civil rights and the nation. The lead plaintiff and namesake of the case was Linda Brown, a Topeka child who was denied the right to attend public school with white children. The Kansas case was consolidated with similar cases filed in the District of Columbia, Virginia, South Carolina and Delaware. Attorney General Harold Fatzer later wrote U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren about the ruling stating, “I think it is right on constitutional grounds. All citizens of the country should be permitted to stand equally before the law and have it administered upon them without discrimination. … If the decision had been otherwise, I feel it would have been a great victory for communistic ideologies in this country, and throughout the world.” Opinion.

Additional Reading: Wilson, Paul E. A Time to Lose: Representing Kansas in Brown vs. Board of Education. University Press of Kansas, 1995.

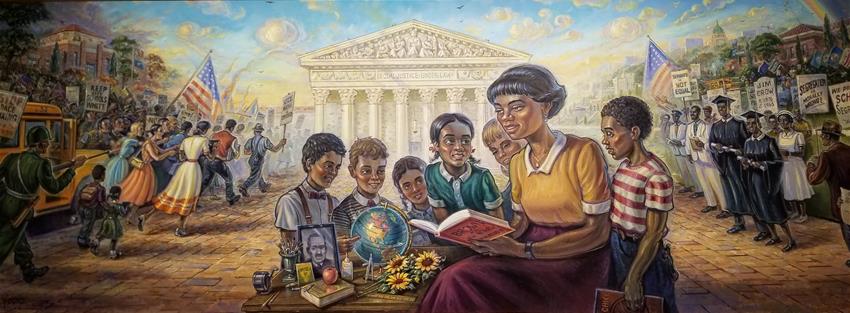

A mural painted in the Kansas Statehouse in 2018 by artist Michael Young depicts the history of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education. The case would find Kansas at the center of one of the most pivotal moments in the history of the civil rights movement of the United States. (Photo credit John Milburn)

1963: Ferguson v. Skrupa. The U.S. Supreme Court reversed a federal district court ruling that had found a Kansas law regarding the business of debt adjustment to be unconstitutional and in violation of the 14th Amendment. The justices ruled that the Kansas Legislature was free to decide that the legislation was necessary and that the law did not violate the due process of law or deny equal protection of laws to non-lawyers. Opinion.

1997: Kansas v. Hendricks. In 1994, Kansas enacted the Sexually Violent Predator Act aimed at involuntarily committing, through civil commitment proceedings, those determined likely to commit additional sexually violent crimes if released to the community at the conclusion of a criminal sentence. The Kansas Supreme Court struck down the Act as violating the due process clause of the U.S. Constitution. The U.S. Supreme Court reversed the Kansas Supreme Court’s decision and upheld the Act. The Court held that further confinement is permissible because it does not serve the retributive or deterrent principles of the justice system and does not implicate double jeopardy. The majority also found that the statute comported with due process requirements. Opinion.

Additional Reading: Stovall, Carla J. “The Privilege of Arguing before the United States Supreme Court.” University of Kansas Law Review, Vol. 46, Issue 1, 1997.

2001: Kansas v. Colorado. The ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court addressed a long-running dispute between Kansas and Colorado that dates to the turn of the 20th Century over use of the Arkansas River. Kansas filed suit in federal court in 1985 alleging that Colorado was using more water than allowed under a 1949 compact between the states. Kansas asserted actual damages related to crop losses caused by the reduced availability of water. The U.S. Supreme Court agreed with Kansas and also rejected Colorado’s claim that such litigation was prohibited under the 11th Amendment. As a result, Kansas was allowed to collect damages and interest for lost crop yields dating to 1985 when the lawsuit was filed. The ruling also states Colorado had been in violation or should have known it was in violation of the compact as early as 1969. A special master had been appointed in the case to determine damages and a settlement between the states. Opinion.

2002: Kansas v. Crane. The State of Kansas appealed a Kansas Supreme Court ruling regarding interpretation of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1997 opinion over the state’s Sexually Violent Predator Act (SVPA). In Kansas v. Hendricks, the court had ruled that the act was a civil rather than criminal proceeding and did not violate a defendant’s due process or create double jeopardy for the crimes. In Crane, the Kansas Supreme Court overturned a lower court decision to confine Crane in an attempt to once again block enforcement of the SVPA law. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Kansas Supreme Court misread the Hendricks ruling. Opinion.

2005: Wagnon v. Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation. Officials with the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation, located in northeast Kansas, filed for injunctive relief in federal court to prevent the State of Kansas from imposing motor fuel taxes on the sale of fuel at the Nation Station store on the tribe’s reservation. The case was dismissed by the federal district court, upholding the state’s right to impose the tax. The tribe appealed to the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals, which reversed the decision and the Court ruled the tax impinged on the tribe’s sovereignty. The U.S. Supreme Court heard the case in 2005 and reversed the appeals court, saying that the Kansas tax was applied indiscriminately and therefore did not violate the tribe’s sovereignty. Opinion.

2006: Kansas v. Marsh: The case involved an appeal by Michael Lee Marsh II who claimed that the Kansas death penalty statute established an unconstitutional presumption in favor of death by directing imposition of the death penalty when aggravating and mitigating circumstances are equal. Marsh was convicted in 1996 for the murders of Marry Ane Pusch and her 19-month-old daughter. The Kansas Supreme Court agreed on grounds that Marsh’s Eighth and 14th Amendment rights were violated and ordered a new trial. The state appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court which, in an opinion written by Justice Antonin Scalia, reversed the Kansas Supreme Court by holding that the state’s death penalty law was constitutional. The Court said that the state must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that aggravating circumstances exist in the case and are not outweighed by mitigating circumstances, or if the jury is unable to reach a unanimous decision in any respect. Furthermore, a jury’s decision that aggravating and mitigating circumstances are equal is not a decision, much less a decision for death, adding that “weighing is not an end, but a means to reaching a decision.” Opinion.

2009: Kansas v. Ventris: Donnie Ray Ventris appealed his conviction for aggravated burglary and aggravated robbery on the grounds that statements he made to an informant in his jail cell prior to trial were inadmissible and in violation of his Sixth Amendment right to counsel. The Kansas Supreme Court agreed, ruling the statements were inadmissible, even for use to impeach witnesses. The state appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. The court, in an opinion written by Justice Antonin Scalia, held that while statements made to an informant could not be used as evidence, they could be used by the state to impeach a witness. In his dissent, Justice John Paul Stevens said use of “such shabby tactics” as allowing prosecutors to cut corners and obtain evidence against a defendant without counsel “taxes the legitimacy of the entire criminal process.” Opinion.

2012: National Federation of Independent Business et al. v. Kathleen Sebelius, Secretary of Health and Human Services. Twenty-six states joined a lawsuit with individuals and independent business organizations against the federal Department of Health and Human Services challenging the constitutionality of provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the act’s “individual mandate” that requires most people to either purchase health insurance or pay a penalty to the federal government but struck down as unconstitutional the requirement that states either expand their Medicaid programs or lose all federal Medicaid funding. Opinion.

2013: Kansas v. Cheever. The U.S. Supreme Court vacated a 2012 Kansas Supreme Court decision that had overturned the conviction and death sentence of Scott Cheever. The Court held that there was no Fifth Amendment violation when Cheever was tried and convicted of the 2005 shooting death of Greenwood County Sheriff Matt Samuels. The issue was whether Cheever’s rights were violated when prosecutors used a court-ordered psychological examination as rebuttal evidence to the defense’s expert witness. Opinion.

2014: EPA v. EME Homer City Generation. Kansas joined a challenge filed by state and local governments seeking to prevent enforcement of mandated emission reductions ordered by the Environmental Protection Agency. At issue was the EPA’s authority to compel by rule and regulation neighboring states to reduce emissions or face federal penalty without the opportunity to file an additional implementation plan. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Clean Air Act does not require the EPA to allow states to file a second State Implementation Plan after the agency has determined interstate pollutant obligations under the Good Neighbor Provisions of the Act. Opinion.

2015: Kansas v. Nebraska and Colorado. Kansas and Nebraska filed claims against each other in the U.S. Supreme Court over the use of the Republican River. The river, which begins in Colorado, which flows east through Kansas then into Nebraska and back into Kansas, is governed by a compact among the states that was enacted in 1943. A special master was appointed to hear the claims. The special master determined that Nebraska consumed 17 percent more water than permitted under the compact during the time period in question. The U.S. Supreme Court ordered financial compensation for Kansas, approved disgorgement of an upstream state’s unjust financial gains from overuse of water, and required Nebraska to take steps to prevent overconsumption in the future. Opinion.

Additional reading: McAllister, Stephen R. Can Congress Create Procedures for the Supreme Court's Original Jurisdiction Cases? 2009, www.greenbag.org/v12n3/v12n3_mcallister.pdf.

2015: ONEOK, Inc. v. Learjet, Inc. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that states are not preempted by federal law from enforcing state antitrust law against natural gas producers. The preemption issue arose in multidistrict litigation filed by retail buyers of natural gas against the ONEOK, Inc., corporation and several other firms. The plaintiffs, which included several Kansas entities such as school districts and large industrial consumers, argued that natural gas pipeline companies were unlawfully manipulating prices, while the defendants argued that the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission held exclusive jurisdiction over such rate disputes and state-law claims were preempted. Kansas Attorney General Derek Schmidt filed an amicus curiae brief in the case, on behalf of Kansas and 20 other state attorneys general, opposing preemption and arguing that states could enforce their laws against these sorts of practices. The Supreme Court took the unusual step of allowing Kansas to present its case during oral arguments. Kansas entities were able to recover more than $1.75 million as part of the antitrust lawsuit. Opinion.

2015: Michigan, et al. v. Environmental Protection Agency, et al. Kansas joined Michigan and other states to challenge the legality of new EPA regulations governing coal-fired power plants in the Midwest, arguing that the unlawful regulations would increase electricity costs for consumers. The Supreme Court held that EPA had unlawfully failed to take into account the economic costs of imposing the new regulation and to weigh those costs against the anticipated health or environmental benefits of the regulation. Opinion.

2016: Kansas v. Jonathan D. Carr, Reginald Carr and Sidney Gleason. The U.S. Supreme Court heard the state’s consolidated appeal from Kansas Supreme Court decisions that had reversed the death sentences of each of these capital murder defendants. The U.S. Supreme Court reversed the Kansas Supreme Court decisions, holding that the Eighth Amendment does not require judges to instruct jurors that mitigating factors need not be proved beyond a reasonable doubt. The U.S. Supreme Court also ruled that the Constitution did not require Jonathan and Reginald Carr’s sentencing proceedings to be conducted separately. Opinion.

2018: National Association of Manufacturers v. U.S. Department of Defense. Kansas was nominally a respondent along with 28 other states supporting the National Association of Manufacturers in their challenge to a federal rule regarding the Clean Water Act definition of the “waters of the United States”, or WOTUS. The question before the U.S. Supreme Court was whether a challenge to a rule redefining the WOTUS in the Clean Water Act fell within the exclusive, original jurisdiction of the circuit courts of appeal. The Supreme Court agreed with the states and ruled challenges must originate at the federal district court level. This outcome led to an injunction being issued in favor of Kansas by the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Georgia blocking implementation of the Obama-era rule. Opinion

2020: Kansas v. Garcia. The U.S. Supreme Court reversed a Kansas Supreme Court decision that had held that federal immigration law preempts state identity theft prosecutions in certain employment settings. The case involved individuals who used stolen identities in order to gain employment. The state argued that the although the state was preempted from prosecuting the falsehoods on federal work-authorization forms, the defendants were prosecuted for using the same stolen information on state and federal tax forms which Kansas could prosecute. The Court agreed that Kansas could prosecute the cases. Opinion.

2020: Kansas v. Kahler. The U.S. Supreme Court affirmed a Kansas Supreme Court ruling in the capital murder conviction and death sentence of James Kraig Kahler, holding that the Kansas mental disease or defect statute was constitutional and did not violate Kahler’s due process rights. In the 1990s, Kansas adopted a revised form of insanity defense, which is now referred to as the “mental disease or defect” defense. Unlike in the majority of states, a criminal defendant in Kansas may be held culpable if he does not understand that his actions, although against the law, are also morally wrong. Kansas is one of several states that does not allow acquittals of defendants who do not recognize that their actions are morally wrong because of mental illness. Opinion.

2020: Kansas v. Glover. In the final case of three from Kansas during its 2019 term, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed a Kansas Supreme Court decision by ruling that it was reasonable for a Douglas County sheriff’s deputy to suspect for purposes of a traffic stop that the individual driving a pickup truck during a 2016 traffic stop was the owner of the vehicle. The Court held that “the inference that the driver of a car is its registered owner does not require any specialized training; rather, it is a reasonable inference made by ordinary people on a daily basis.” Opinion.